by Michael

Nothing in this post is legal advice. All cases’ fact patterns are different, and competent attorneys will use their own trial strategy as it applies to their fact pattern.

This post was written in September 2023, so the technology should be expected to evolve and change over the coming years. There is also no published caselaw at this point in time, so future readers should consider any definitions of technical terms that arise after this posting.

How Deepfakes are made

Before explaining deepfakes, a lawyer should understand the basics of how a deepfake operates. In simple terms, deepfakes are made in two steps: First, the acquisition and identification of data input and then the production of the deepfake output. (The term “deepfake” is often used to refer to both the producing program and the produced video itself).

The input of data uses a neural network, which is a program that receives data and then identifies connections across the different sets of data by examining what the data have in common. A neural network that’s been given thousands of pictures of faces might observe that the images tend to have similarly-colored pixels in the shape of a nose, eyebrows, and mouth. The neural network is then able to spot other faces in new images by looking for similarly-colored pixels in the shape of a nose, eyebrows and mouth like what it’s already seen. It’s no different than showing a baby several pictures of cats and asking him whether an unfamiliar picture also contains a cat.

The production process of deepfake videos takes the neural network’s observed connections and uses them to produce images that follow those observed connections. The obvious end result of this is that one can feed pictures or video of a person’s face into a deepfake program and receive artificial pictures or video of that person from the program that are lifelike and very believable because they copy many of the identifiable facial features that were observed by the neural network. It essentially uses faces to make more faces.

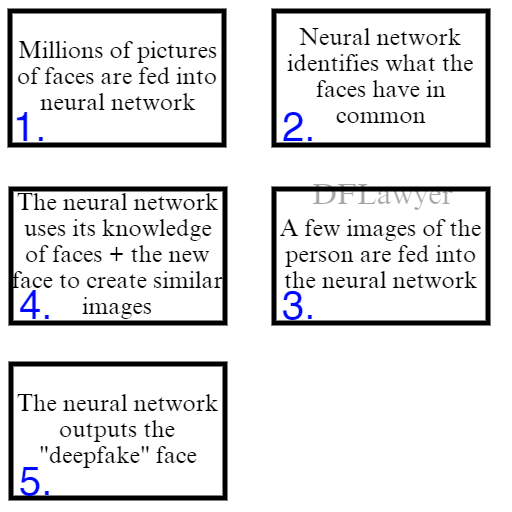

This infographic hopefully demonstrates this process. Feel free to create a similar one for your own purposes.

This is deeply boiled-down, and readers with a special interest in deepfakes will certainly not find it satisfactory. Here’s the Wikipedia page for deep learning algorithms if its intricacies are what you’re after.

When explaining deepfakes to a layman, juror or layjudge, there’s two basic strategies to pick from. The first is the simple input-output strategy. The second is the overly complicated neural network strategy. Trust me, you want the simple one.

How to Explain Deepfakes in Trial as Plaintiff’s Counsel

Input-Output (Simple)

Jurors and layjudges are rarely educated in the intricacies of modern artificial intelligence, let alone the details of the neural networks used to produce deepfakes. The simple approach will be the most successful in nearly all of your cases no matter the experience of your audience. It’ll also keep you from having to spend client money and juror patience on an expert witness.

In the simple method, your choice of explanation depends on the technical abilities of your jury. For jurors that are more up-to-date with technology or are able to understand more technical concepts, it’s best to analogize deepfakes as a machine that takes inputs of the subject and produces outputs based on “algorithms”. For jurors that aren’t up-to-date with technology or haven’t spent much time with technical concepts (often the older crowd), it’s best to analogize deepfakes as a sort of “caricature artist” that can look at a person and convincingly draw them doing something that they didn’t do. Selecting between these methods is a judgement call that you’ll have to make on the fly.

Technical Jurors

Explaning Deepfakes

If your audience strikes you as having been technically-proficient at some point in life, the first simple approach is your better option. This approach is the most accurate to the facts and will stand up better against objection and on appeal. When explaining the creation of deepfakes, explain it as a process where images of the subject are used as inputs into the algorithms that copy their face and output similar images. Use technical terminology like “inputs” and “outputs” so there’s less for the opposing counsel to object to – those terms are broad and can be slippery in their definitions, so you have more to work with to overcome an objection. Use an infographic like the one above to demonstrate your point if need be.

After explaining the basics of deepfakes, you’ll need to connect it to the victim to humanize the procedure. Victim’s counsel should create and display as demonstrative evidence a few deepfakes of the victim doing interesting but obviously fantastical things, like walking on the Moon or replacing an actor in a well-known movie scene. This demonstrative display helps concretize of the jury’s understanding of deepfakes. Use these displays to underline the point that while we know the victim is obviously not the person who did that thing, someone without context (such as someone who hasn’t seen the movie containing the deepfaked scene) could see the deepfaked clip or a photograph from the clip and conclude that it actually happened.

Be sure to explain that counsel created these deepfakes, and that they’re made to explain what deepfakes are. Jurors may get confused which deepfakes are the actual cause of the suit.

Then drop the hammer. If the deepfakes at issue are at all shocking, pornographic, or dignity-reducing introduce them to evidence and publish them in as physically large a size as possible. You want to play up whichever emotional factor is most useful here. Capitalize on those emotions by humanizing your victim and their emotions during the process if it’s that kind of case. You’re not proving the legal harm yet (depending on your claim) but you are proving the emotional harm to win over the jury.

The overarching goal is to first make it clear to the juror that deepfakes appear believable without context, and then to get the jury to feel the emotional harm that the deepfake caused. If they feel that harm they’re more willing to accept that the deepfake caused material harm as well.

Example scenario

Suppose your client is a known female celebrity, and the lawsuit is over defamatory deepfaked images of your client in sexual congress with another man who is not her husband. You might:

- First display deepfakes of your client shaking hands with a celebrity to drive home to the jury that the images are clearly fantasy even though they look believable.

- Then explain we only know that they’re because your client has never met the person. Explain that someone who doesn’t know that nobody in the image has ever met could conclude it was a real image.

- Then display the deepfakes of the sexual congress. Emotionalize how your client felt upon seeing these deepfakes.

- Explain the harm of your case: that someone who doesn’t know the client wouldn’t know that these images are fake, and would assume that this image depicts a real event. That assumption caused the harm from the defamation, and your client is owed damages.

From there, your primary argument has been made. The jury’s understanding of deepfakes should be fairly solid, and hopefully paid enough attention so as to mentally reconstruct your argument in deliberations.

One Note

Early in the adoption of deepfake and AI-generated image technology, a popular notion spread that AI-generated images had certain consistent flaws in their outputs. Most people have heard that these images can’t consistently “draw hands” or similar body parts. This is no longer the case, and many AI image generators can realistically replicate the human body with ease.

Plaintiff’s counsel may need to specifically address and debunk this point at some point. The last thing you need is a juror who decided the deepfakes at issue were actually real pictures and returned a verdict against you on that basis.

Non-Technical Jurors & Layjudge

If you’ve pulled a jury or layjudge who calls their grandkids for help finding “The Google” then using the non-technical analogy of the “caricature artist” is better.

Your argument should be simply that deepfakes are a lot like a skilled caricature artist. The artist in your analogy has looked at the person from a few angles and draws that person doing something they didn’t do, and draws it very well. The drawing is believable and identifiable as the client, but it’s not real. The problem is that the artist drew your client doing something that harmed your client.

(A layjudge would likely understand the analogy as soon as you make the “caricature artist” connection due to years of working with analogies as a lawyer. Jurors will have a harder time.)

From there, continue with your explanation in the same manner as was explained in the Computer-Savvy Jurors section. Show the more “normal” deepfakes first to demonstrate that they’re believable, and then drop the hammer on the deepfakes at issue.

Neural Network (Complicated)

Over time the general population will become more literate in issues of artificial intelligence, and may already know some of the more basic facets of deepfake production. This opens up the possibility for deepfake complaints to litigate more narrow and complicated issues that are now palatable to the layperson jury. Plaintiff’s counsel may even find it beneficial to litigate over a more narrow component of deepfake production instead of the product itself. One could imagine a scenario where a deepfake lawsuit comes down to how the neural network obtained the data it was individually trained on or some other niche issue.

Even if the general population becomes competent with these concepts, counsel’s best shot is simply to not explain deepfakes themselves. Get an expert witness on the stand who actually possesses the deep knowledge of deepfakes (pun intended) and guide the expert witness through the intricacies at issue. Expert witnesses create less room for objection (or at least, if they make a mischaracterization of something, opposing counsel is less likely to have the same technical knowledge on which to object) and will impress the jury with the level of sophistication that goes into making deepfakes believable.

IN CONCLUSION

The primary hurdle of explaining deepfakes as plaintiff’s counsel is the technical understanding of deepfakes and the general public’s lack of awareness about how they can be used. The secondary hurdle is convincing the jury that the deepfakes are believable enough to have caused the harm. Learning about deepfakes and seeing them in action should do the trick.

Leave a comment